Making Models and Props (part 3)

Model-making was an interesting, challenging, creative, and very cool profession; however, as time went on, I became increasingly concerned about health-related issues associated with that particular line of work. Although I loved making models and props, I decided to move out of that field of the business and focus exclusively on animation. Here are examples of my last model-making projects.

In 1988, I assisted Niels Nielsen in building a prototype of a helicopter model created for presentation to the United States military as a possible future design. Not only did we fabricate the helicopter from scratch but we incorporated the motorized rotors and lighting as well. Unfortunately, we worked in a small room with poor ventilation and used many materials such as Bondo, urethanes, and glues that emitted toxic fumes. To make matters worse, I managed to cut my finger in half with an X-acto blade, an accident that required a trip to the emergency room! That particular project illustrated a stark reminder of the occupational hazards involved in professional model-making. Our model was ultimately filmed by cinematographer Mehran Salamati, who used a motion control system against a blue screen to composite in front of a sky background. I never saw the completed film.

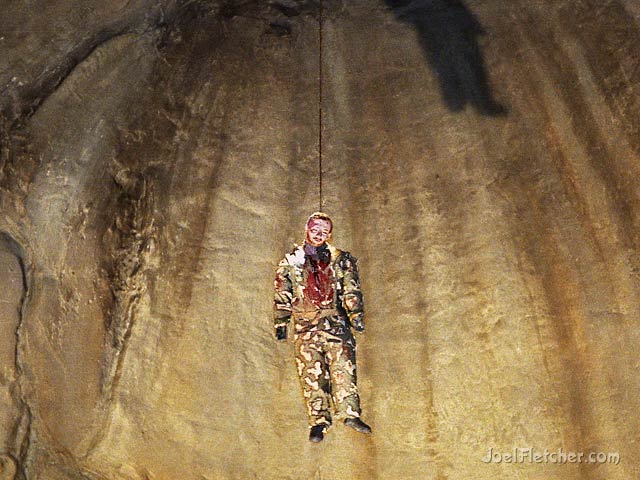

Sylvester Stallone's Rambo movies were very popular in the 80s, and I was fortunate to have worked on some great scenes from 1988's Rambo 3. Introvision International provided visual effects for the film, and one of the key scenes involved the spectacular death of the badass Russian soldier Kourov. In that sequence, Rambo fights Kourov near the opening of a subterranean cave. After a failed attempt at choking him with a rope, Rambo pulls the grenade pins attached to Kourov's vest then knocks him down a hole into the cave, ultimately hanging and exploding him at the same time. That novelty death scene was actually filmed using miniatures by Introvision, the company which hired me as a sculptor for the project.

My first assignment was to pre-visualize the cave as an accurate miniature replica of the filming site known as the Bell Caves in Israel. The cave miniature needed to be quite large, about 12 feet high, so to assist in its construction I sculpted a much smaller 2 foot reference model out of green foam. Once the reference model had been approved, the actual model for filming was fabricated by Richard Kilroy under the supervision of Tim Donahue and Gene Rizzardi. Basically, it consisted of a rebar frame covered with chicken wire, sprayed with gunite cement, and sculpted with plaster for the final detailing. The result was a robust, fireproof miniature set that could withstand any pyrotechnics to be used during filming.

The most enjoyable part of the gig was the sculpting of a miniature Kourov. Relying on photos of the actor in costume, I used Roma clay to create a 12-inch replica. After molds had been made, the character was cast in urethane foam. Art director Anton Tremblay handled the paint job and all of the clothes which were made out of paper towels. The main objective was to use lightweight materials that would explode easily and safely. After the camera crew had filmed the shot, which of course utterly destroyed the Kourov model, a crew member came to the model shop and announced that the director wanted to shoot another take. Of course, no one had told us they might shoot multiple takes so we were not prepared with additional models. Anton and I immediately scrambled to create more Kourov miniatures, each of which required many additional hours to recreate.

The exploding Kourov looked amazing in the movie, but I was personally disappointed that the viewer could not see the carefully crafted Kourov model before it blew up. Originally, I thought that the editors had cut the shot right on the blast, but I recently examined the movie frame-by-frame and there had been about two visible frames before the destruction. I felt let down because a lot of hard work and careful attention to detail had gone into that unique model, and it was never really visible in the final cut. Oh well, that is the motion picture business!

In 1990, Introvision International hoped to get the special effects work for an upcoming blockbuster called Isobar, starring Sylvester Stallone. Most of the action in the Isobar script was to happen on a futuristic train, and I was hired as part of a small crew to fabricate the train in miniature for a proof-of-concept test film. Anton Tremblay created blueprints of the train and supervised the project. My main involvement was to construct the locomotive. The main form was sculpted out of foam which was then used as a pattern over which sheet styrene was vacu-formed into shape. That method resulted in a nice hollow basic structure, which I then detailed with various styrene plastic parts. The model had working lights and it had to roll on specially designed rails; accordingly, we could not use any commercially available model railroad parts. The train was filmed and composited over footage of downtown Los Angeles using the "Introvision Process." Alas, Isobar never went into full production. This photo is a rare remnant of a movie that never really happened!

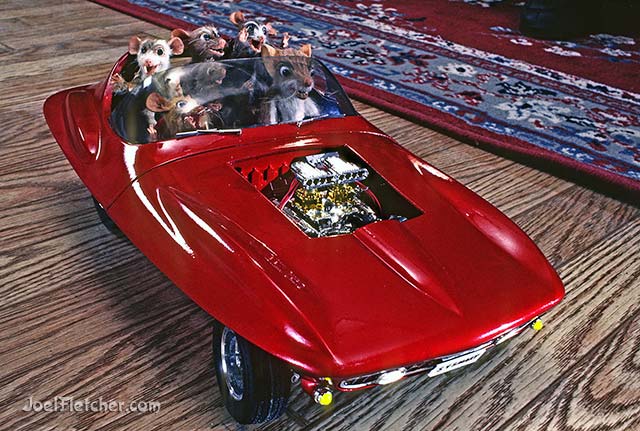

The 1990, ABC television special Ralph S. Mouse required a "sports car" for the ending sequence. Although hired as a stop-motion animator, I jumped at the chance to also create the Laser XL7 Roadracer for the film. Being a hot rod and show car enthusiast, I wanted to deliver a bit more than a mere sports car. I used kit-bashing techniques to construct the vehicle. By chopping and combining at least three different 1/12 scale car kits, I was able to create a unique hot rod for the main character, Ralph S. Mouse. The hot rod featured functional steering, spring suspension, and working lights. Ralph cruised in style!

In 1995, a company called Interfilm was making "interactive movies," a new concept that never really took off. Their third film was Bombmeister, a title that basically tells its story. Anton Tremblay was the production designer who hired me to make a replica of a vintage slot machine. The script called for the blowing up of a slot machine, an action which could not be achieved using a real one made of cast iron and wood and weighing a ton. Materials for the replica were chosen to be as lightweight as possible. The flat surfaces were easy to duplicate as they were made of foamcore. The compound shapes were sculpted out of foam and covered with thin styrene plastic sheets via a vacuform machine to develop a smooth finish. Anton designed the cool graphics, including skulls which were not on the original. I was very pleased with how well the fabrication compared to the real thing. Once again, however, my handiwork was blasted to smithereens. (This result reminded me of a favorite childhood activity where I would build model kits then destroy them with firecrackers after I grew tired of them!) Unfortunately, Interfilm failed as a viable company and Bombmeister was never released, although the movie was probably completed.

1995 marked the end of my model and prop making career because I was hired by Walt Disney Feature Animation to be a computer character animator. After that, I stayed in the digital animation realm and never looked back until…

After many years away from the business, my old friend Anton Tremblay briefly lured me out of model making "retirement" to help him with a print advertisement for a pharmaceutical company in 2007. The ad illustrated an outdoor scene that featured fireflies which, on closer inspection, were actually immunoglobulin molecules. My contribution was to fabricate the Y-shaped molecules, based on the agency artwork. To create the ovoid shapes, I used a cobbled together lathe made from a slow-moving electric drill. Using a template for accuracy, this allowed me to slowly build up a nice symmetric oval out of bondo. The kidney- shaped pieces had to be modeled freehand. Silicone molds were made in order to make multiple copies out of two-part urethane casting resin. The bottom pieces were cast in clear resin so they could be lit up for the firefly effect. Anton completed the final paint job and installed the working lights. Our model could have been rendered via computer, but the agency, to their credit, wanted the look of an actual photographed prop for their ad. This project had extra significance for me as I had been previously stricken with an MRSA super bug in 2001. Near death despite massive doses of antibiotics and surgery, I was revived and ultimately recovered after the doctors initiated a dosage of intravenous immunoglobulin. It was a meaningful coincidence for me to create that model!